April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

T.S Eliot

From a conversation between Benedetta Donato, curator and editor, and Anna Maria Antoinette D’Addario, held for the book presentation which took place at the Photolux Festival in Lucca, Italy, on November 23rd. Anna’s dummy was the winner of the PhotoBoox Award 2019.

Benedetta: This project was created in response to a terrible and tragic event, in the work you reference this by describing the moment that you received the phone call that told you what had happened.

Your work is an introspective and delicate expression of loss, pain and the weight of memory and it is from memory, the family photo album and photographs of landscapes of your life that form the content of the photo book. Can you tell us why you began this work.

Anna: This work began as a response to the sudden and violent death of my sister in 2015 and gradually became a path to live and make sense of life again. It was an act of resistance, an attempt to speak in the face of silence. Bookmaking became a means of acknowledging grief, searching to create a vital and necessary mourning space to mediate my sister’s loss – through it I was provided a place to revisit the past and breathe life into the present.

I come from a large family and Daniela was my closest sister. Older than me by only a year and a half, the two of us shared the same history and childhood and the same parents. With her murder, time stopped, all became fractured and fragmented, I, together with my mother and all who loved her, were drawn into an obscure world without her, a world broken and changed. A world of trauma, loss and profound grief.

Through the book I attempt to memorialise but also to fight against amnesia, to prove a relationship that was understood between my sister and myself and show how her presence lives on in my life. I believe a memorial work makes a symbolic space to battle amnesia, it asks us not to forget the past and what it has meant to us. What we have inherited from it. It also asks people to confront what has happened, to not ignore what is hard to bear.

B: Could you explain the choices you made to communicate and express your history and childhood with Daniela? For example in the bookwork you have chosen not to include any images of Daniela as an adult.

A: Over the past years, after we had discovered what had happened to Daniela, and then when the perpetrator was apprehended, there was continuous media cover, which extended throughout the court proceedings. Every time an article was published an image of my sister was used, and yet often the image of the man who had taken her life was blurred. Daniela through her image was reduced to a series of violent details of her death, often details we didn’t know and found out through the media. She became a statistic, a number to add to the growing amount of women killed in Australia at the hands of violent men.

A: Over the past years, after we had discovered what had happened to Daniela, and then when the perpetrator was apprehended, there was continuous media cover, which extended throughout the court proceedings. Every time an article was published an image of my sister was used, and yet often the image of the man who had taken her life was blurred. Daniela through her image was reduced to a series of violent details of her death, often details we didn’t know and found out through the media. She became a statistic, a number to add to the growing amount of women killed in Australia at the hands of violent men.

The media also referred to the perpetrator as her partner. They would publish images of the two of them together. Yet they were not partners. They had a brief affair, which she ended, and he became obsessed. Throughout this time, we could not speak to the media, neither my mother or myself. I desperately wanted to change the descriptions of my sister. I can not describe the pain of seeing someone you love reduced, their identity erased after the knowledge that their life has been violently taken. Daniela was described as a beautiful girl in the papers, she was more than that. She worked in government to report on the treatment of asylum seekers, an issue that is very difficult in Australia due to the heavy policies and laws introduced by our political leaders, she was a dancer, she loved to paint, she wrote, she was complex, she was highly intelligent. She was more than a beautiful girl.

Before the sentencing date, I chose to write to the paper, to a journalist my mother trusted, to talk about the damage this man had done and to try to regain an idea of my sister’s identity and who she actually was. I choose to do this anonymously as I did not want to speak out publicly, it was too difficult, I was grieving and dealing with acute trauma. At the time of my sister’s death two women per week were killed by men they had known. She had become a symbol for a pressing national issue.

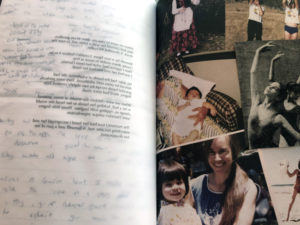

My sister was thirty-five when her life was taken. Her future has been lost and the past and our childhood has been altered and affected. The knowledge and weight of our history has only one side now, one gaze, and one recollection. Through the book I searched to reclaim her identity through our childhood and her place in our shared past. I used childhood as a form of protest to counteract how her image was used and narrated in the media. In this instance using her adult image felt like another violation. In the book, images of myself as a child – with just one on the precipice of adolescence – accompany those of Daniela, we break silence together, identities intertwined.

B: This work was also the focus of your thesis and research paper for your Master of Fine Arts at Sydney College of the Arts. In the paper you write that photography is a tool to explore the unknown, to work on memory. You talk about how the act of photographing was cathartic. What meaning did it have for you to revisit your childhood places and what did you hope to evoke with your images? In your paper you wrote a lot about thresholds, could you explain this further?

B: This work was also the focus of your thesis and research paper for your Master of Fine Arts at Sydney College of the Arts. In the paper you write that photography is a tool to explore the unknown, to work on memory. You talk about how the act of photographing was cathartic. What meaning did it have for you to revisit your childhood places and what did you hope to evoke with your images? In your paper you wrote a lot about thresholds, could you explain this further?

A: In his poem ‘In a Dark Time’ Theodore Roethke writes, ‘The edge is what I have.’

In the presence of trauma, loss and deep grief we experience the world as perpetual chaos. We experience our lives at such times, fractured from the meaning they once held, as confused, uprooted and disordered. Within this disordered world, there is a search to restabilise ourselves, to reassemble the fragments of our identities, the pieces of what our lives once meant and now mean to us. A need to seek stabilising forces, reaching for ways to reorder the chaos and navigate the confusion.

The dummy that I sent into the PhotoBoox Award was a modified version of a handmade artist’s book that I worked on while investigating my artistic process during my research degree. Evoking important childhood places I shared with my sister through photographic fragments allowed me to create visual ‘thresholds’ where memories and meanings I shared in the past with my sister were able to meet with the disorder and trauma of the present. Through photography I was able to find a way to slow and stop time to deal with the trauma against the forward current of life. Re-ordering these moments in the bookwork aided me to move forward from the fragmentation of the past and reconstruct and preserve a story and a past that had been fractured by the trauma of my sister’s death.

The act of making a book, working in a real dimension with images strewn across the floor, piecing fragments together, inserting gatefolds, working with vellum paper, creating a concertina is a cathartic process but it was also confronting and difficult. There is a lot going on in the first version, various concepts, because with the artist’s book while also creating a work of elegy and love, I was also trying to express the fracture of trauma, the impact of violence and the depth of that sorrow. In my thesis I talk a lot about thresholds and how art, or poetry, or literature can take us to the edge, to help us make an understanding of the unknown without needing to be thrown from a precipice. Extreme trauma and grief throws us over the edge, we are thrust from this threshold without choice and with violence. To survive, to make meaning once again of life one needs to find stepping stones out of the darkness.

The act of making a book, working in a real dimension with images strewn across the floor, piecing fragments together, inserting gatefolds, working with vellum paper, creating a concertina is a cathartic process but it was also confronting and difficult. There is a lot going on in the first version, various concepts, because with the artist’s book while also creating a work of elegy and love, I was also trying to express the fracture of trauma, the impact of violence and the depth of that sorrow. In my thesis I talk a lot about thresholds and how art, or poetry, or literature can take us to the edge, to help us make an understanding of the unknown without needing to be thrown from a precipice. Extreme trauma and grief throws us over the edge, we are thrust from this threshold without choice and with violence. To survive, to make meaning once again of life one needs to find stepping stones out of the darkness.

For my practice, the illumination of memories through the photographic provided me those steps to move forward. With this work I hoped, and continue to do so, that it might function as a sort of threshold, a mourning space and a memory space that provides solace for others who have experienced a similar loss. Or also allow others who have not, to understand what the impacts of that loss may be. To say it is ok to grieve, to be open about violence and its effects. Even if society doesn’t allow it, or even condones it. These are conversations we need to be having.

—

We at ceiba have worked with Anna on the new version of the book, which is now available to order in our store. We want to thank Anna, and also Photolux and Grafiche dell’Artiere, without whom we could not have made the book as it is now, with the material we chose to use.

wonderful work I really want to see the final book…